Still Zombie after all these years: An Interview with J. Yuenger

White Zombie was a strange and fun creature in the noise and metal landscape of the late 80s and early 90s, maybe because it was never really clear what was going on. The pummeling riffs said "metal," the disturbo-giddy aesthetics, mostly the brainchild of one Rob Zombie, screamed "B-movies, circus show, and freak show," and the melange of cultural references and moans said, well, it said just that.

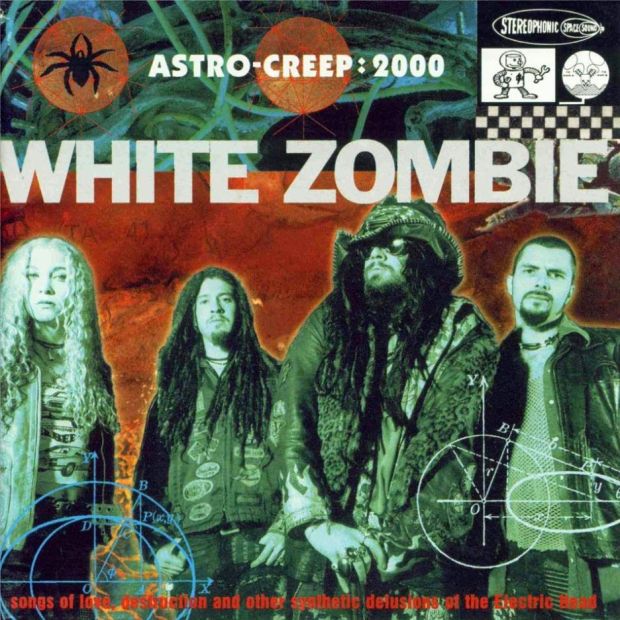

And it was this apparent lack of clarity that was a big part of the appeal of this wacko band, and a sizable part of what would become its success. From the post-Beavis-and-Butthead-explosion to the multi-platinum status of Astro Creep: 2000, which is nearing its 20th release anniversary. Ultimately, perhaps it's the same elusive character that caused the Zombies to evaporated from public consciousness following the band's breakup, as if everyone woke up to realize it was just all a crazed 90s moment, picking up our clothes and tip toeing out the room.

As you may have guessed by now, however, they never dissipated from my consciousness. Mainly because of their amazing, and, yes, insane, music, probably also because of their intense visuals, and maybe just slightly because I had a crush on Sean Yseult. But they were smart, sharp, wholly self-aware and mainly: fun. Say what you will about the world of heavy/metal music, bands that exude anything remotely like exuberance are very rare. By the way, it's exactly the utter lack of said exuberance that, at least in my eyes, causes Rob Zombie's solo efforts to fall flat. It's not fun anymore, it's business, which only amplified just how great the albums were when they were still all together and not standing each other.

FOLLOW MACHINE MUSIC ON FACEBOOK

Now, as part of our program "Ron gets to go back in time," I decided I felt like digging in that odd hole. And, luckily for me, an excuse presented itself in the form of Astro Creep's aforementioned anniversary. I remember where I bought this record (a shop called Piccadilly in Ramat HasSharon, when (Hanukkah, 1995), and how I felt when I heard the first riff hit my neck (pretty good).

So what I did was talk, quite a bit, with J. Yuenger, remembered as just "J," the talented, intelligent, and enigmatic White Zombie guitarist, and one of the people I most wanted to be like in my life (the only man who ever made we want an Ibanez, because of his crazy Iceman). The result is without a doubt the most in-depth interview I have done to date, mainly because Jay had the good fortune of being a part of several significant musical moments or phases in his life: From childhood and boyhood in Chicago's hardcore scene, to metal in early-90s New York, to his present as a producer and mastering engineer at Waxwork Records, a label dedicated to reissuing and remastering old-school-horror soundtracks.

It's a bit on the long side, I'll be the first to admit, but if I were you I'd read it all. Enjoy.

What is your first experience with a specific music or artist or album that kind of really triggered something different for you? That whatever it is your were listening to until that point was OK, what that something really made you feel that "coin dropping" as they say in Israel, a first moment?

Well I became aware of music when I became a teenager, at a very special point in American culture, where, you know, rock music was the predominant thing. Music was everywhere, and rock music was the mode of entertainment for young people at that time. And where I'm from, the Midwest, was a hotbed of Rock n' Roll. When I first started listening to music, which would have been like 1979, something like that, there were quite a few bands who…. Like, you've heard of, you've seen pictures of punk rockers in magazine, and maybe you heard there was something called punk rock, but there was no way to hear what the music sounded like.

But, at the same time, in mainstream music, there were bands like Cheap Trick, like Blondie, like Tom Petty, and you've think "Oh, is this punk rock? Is that what it is?" Because, you know, they had some of the fashion from punk. And so, you could hear these groups on the radio, you started to listen to those groups, and you liked it more than what everybody else was listening to. All the kids in your school were listening to, you know, Led Zeppelin, and on the radio it was just nonstop like Foreigner and Boston, and the huge rock bands of the seventies.

And you started listening to Cheap Trick, and that was the first record I ever bought, Cheap Trick: Live at the Budokan – that group is from where I'm from [Chicago] so they were very very popular. And then, looking around the record store…. I mean, there was no one to tell you anything about music, there was no music blog you could listen to, and mainstream press wasn't covering much outside the parameter. So, you looked around the record store and you found The Ramones, and you listen to this, and this is a revelation, and you found the Sex Pistols. Which was great, but I just remember wanting more, a harder sound, a faster sound, something that contained even more anger than the Sex Pistols.

It's interesting too, because I was at a bar yesterday and they played "God Save the Queen" and then right after that they played "I Wanna Be Sedated," and…. You know how you go some place or you're listening to the music on the radio or the music their playing at some place, you kind of hear the music with fresh ears, I mean, you didn’t choose it, you know? So I was really listening to these things and it was interesting how they're so, the sound of those groups was pretty similar to everything else that was happening at the time. And I was kind of amazed at how subversive they seemed at that time to people, you know? When they really were not that different. They were different conceptually, but certainly the physical sound of them was not. And I remember feeling this way after a while when I was a little kid, where I always wanted something more.

And then one day I heard Black Flag on college radio and it was a huge moment for me, because finally there was a group that was as abrasive as the sound that I had been dreaming of.

Do you remember which song it was?

Yeah, it was "White Minority." It was also some challenging lyrics that were very difficult for the time, you know?

What was it? That the music was abrasive? That the lyrics were abrasive? Or just the whole thing?

The whole thing. I mean, think about something like the English punk groups, like 1977 punk. They used the same equipment that every rock band had been using for twenty years, you know? They had very nice American Gibson guitars, they had very nice beautiful-sounding tube amps. And all of a sudden here comes this band Black Flag, and they have a plastic guitar, and he's playing it thought a solid-state amplifier that he built himself. I mean, that's punk rock. It was a very, very ugly sound, but it was calculated to be ugly, which I really liked when I was a teenager, that really appealed to me.

And this is when you're in Chicago, and, how old are you at that point?

I'm like 13.

Was there something about that experience that not only felt the right amount "more" but that made you want to be involved yourself? Make you feel like picking up a plastic guitar and plugging it into a self-made amplifier?

Well, I already wanted to be involved. That was, again, at that time for a young American, that was the mode of expression. You know, the music scenes drew in a lot more people than just people who liked music. Like every youth cult, it had a huge social component. Every kid who was disaffected found belonging in punk, or some other scene like that.

So I had already wanted to be in a band, but, you know, when you're a little kid, you're not even a teenager yet, you don't have any money, you don't have any power, you can't do anything, and the music you're exposed to is like Led Zeppelin, how can you even imagine that you can make music? Whereas, you listen to Black Flag and you think "Oh, all I have to do is get any guitar and I can probably figure how to do something like that."

And how long did it take you to actually do that yourself? Was Rights of the Accuse your first band?

Yeah, I think I met those guys when I was still 14.

So not long after.

Umm, you know, at this time the big problem was finding out where to go to meet people who like the same things and where to get the records, and that was not easy. It took me a while.

At what point did Rights of the Accused become a real band, a band that tours and plays in front of people.

When I was 15.

I imagine It was a big moment when you guys opened for Minor Threat and MDC, and at this point Minor Threat is a huge band, no?

I mean, you have to put that in perspective. That show, there were probably like 65 people there, so for us this was huge because for local bands there were far less people. For us a really really huge show was when the Dead Kennedys came, and there were like 300 people there, that was the biggest it ever got. So, this is certainly very big for us, that was absolutely our soundtrack of that time, so that was very exciting. The scene was very very small, you know?

But, did that moment become bigger in retrospect? Minor Threat disappeared not long after, and hardcore in general pretty much disappeared not long after.

I mean, at the time you could tell that hardcore was going to…. You know it didn’t disappear, it just passed along to another generation. When I hear the Out of Step record this very much reminds me of high school and looking forward to the end of high school, and it reminds me of the time when you knew that all your friends were going to disperse pretty soon. So, for me the end of the first phase of American hardcore coincided perfectly with high school being over, and people moving away, and that was the exact same moment when everybody kind of stopped listening to punk so much, and sort of growing their hair, or whatever they got into. It was obvious, I think, at the time.

What was obvious about it? Why do you say that?

For a lot of people, you get into punk, you adopt all the punk ideals, and you adopt the punk clothing, and you adopt the punk mannerisms. And then you go through a process of weeding through those things and seeing what actually fits you, and discarding most of it. By the very end of that time, you go to a show, and most people didn't look like hardcore kids anymore, do you know what I mean? It was like everyone was in disguise or something, and it was apparent that something else was coming.

For me, musically, everything was coming. You know, towards the end of the 80s there were so many different things going on. In the mid 80s you would literally have a week where you would go see Metallica one night and go see like Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds the next night, and then you would go see Samhain the next night. It was a pretty great time.

And I can ask you, in light of what you're saying, that it was kind of obvious, because the stereotypical depiction is that it was like a flash in a pan: it can from nowhere, and it went away. And, what you're describing is like more of a process – that it had a limited life span because there so much time people can take on those values without looking around, that it’s a matter of time before they choose something else. So, it isn't that hardcore disappeared it's that the people who listened to hardcore started to listen to other stuff as well.

Yeah, I think also that hardcore served its purpose as a second school for a lot of my generation. You know, today if you want to do something then it's no big deal. If you're a little kid and you want to know how to play guitar your go on YouTube and take lessons, you know? You wanna learn how to hand glide you go on the computer and it tells you what you need to do and where you need to go, and by the end of the day you can be at the hand-gliding shop, you know what I mean?

Whereas, at that time, the culture basically is basically still living in the seventies, when I was 15 years old I pressed my own records and I learned how to work a PA, and I learned how to build a stage, you know, and these are very unusual things for that time, for young people to figure out on their own. I mean, it would have been different if it was part of some music program at a school, or if my parents had taught me those things, but that's not how that happened. The fluidly of that time, when people used hardcore as a stepping stone to playing music, and that's in the past of a lot of people who had become famous in the 90s.

I think that what seems timeless in a way is that you listen back at all those records and you can still get why that was something that blew people minds. That the authenticity about it, I don't know if that's the right word, but it felt real. Maybe because people didn't really know how to play, maybe because they were young, but it felt real. I think that that "real thing" is something people look for in music, and once they find it that becomes very meaningful for them.

Yeah, I think that you know about the music scene, as far as what was happening in the major labels and on the radio in the early 80s, you had to….To be a band on a major label, to put out records, you had to jump through a lot of hoops, and you had to have a lot of corporate people, people who were signing the checks, decide that they wanted to work with you, that they would want you to change this or change that, you know what I mean? Most records from that time, if you actually talk to the people who made them, and I'm talking even about records we would consider to be not cool at all, the people who made the record would say "Well, the record company wanted us to change this song, and the producer made us put strings of violins in this song, they wanted us to change the arrangement of this song." The groups who like absolutely wanted to control their art had to fight really really hard to do it. It was not easy for them.

And you have something like The Ramones, who, when you listen to them now it doesn't sound particularly challenging, but it's really because we've heard it our whole lives, and we're used to it. But, if you really think about it you could get an idea of just how alien that sound was when people heard it in the first time in 1975, they were not really in a major label, they were in Sire. So, you have records with no editing whatsoever, no outside influence, they sounded very very different from records that were out at that time. And they retained that. You know, each group at that time was unique and individual, and you can hear some of those powerful personalities on those records.

Is it fair to say that the next big thing for you was metal and heavy music?

It was one of the things. In the middle of the decade, my friends and I were listening to metal, I mean we were certainly listening to Slayer, Metallica, and a million of those bands. We were definitely listening to Hip Hop. We're definitely listening to old punk. We're definitely listening to pre-punk – everyone loved MC5 in those days, The Stooges, The Velvet Underground. We were getting into old hard rock, everybody loved Black Sabbath. Everybody was certainly getting into the new alternative guitar groups, everybody loved Dinosaur Jr., My Bloody Valentine. Metal was one thing. So this is something that seemed normal to me.

You know when people first heard [White Zombie], they were mystified by it because they couldn't tell whether it was metal or not. The simple answer to that is "It's metal, but it's also other things. Why is that challenging to you?" [Laughs]. It's normal now, but then it was not.

That's a perfect segue for me, because in my eyes, a lot of bands seemed to straddle a line that they don't so much anymore, it seems like a much more niche music market now. It seemed like an historical moment almost when bands like your band, and bands like Faith No More, and bands like Fugazi, for me at least, bands that were all over the place, and they got away with it. They were successful by being all over the place, whereas later that became less the case. Does that make sense to you at all?

Yeah, sure.

What kind of influences you feel you brought to the band, you part in that happy mess that White Zombie ended being?

At that time, and you can hear it very clearly on La Sexorcisto, we're obviously very into Slayer, I mean, we got Andy Wallace to produce the records because we loved his Slayer records. We're very into hip hop, I mean, Sean [Yesult] wasn't really, but Rob and I listened to hip hop nonstop. You have to remember that this is New York City in 1991 or 1990. Once again, we're at the right place in the right time to receive culture.

What hip hop are you listening to

Public Enemy, things like that. And you can hear Public Enemy in those songs, sort of like. We're not really using loops at those point, because we still don't know how to do that [laughs], but we're definitely starting to think about using noise samples and other samples as well. And we're still coming from a culture of, you know, we like the Butthole Surfers, we like the Birthday Party, we like The Cramps. These influences are not all showing in the music, but they're showing in the aesthetic and in the general vibe of that thing.

I mean, The Cramps seem to me, aesthetically, to be a huge influence. The Cramps were like the White Zombie of the early eighties. That whole horror/rock thing.

Absolutely. I mean, you asked about… What's that expression you said you use in Israel for when something changes completely?

The coin drops?

The coin drops, yeah. For me, I was telling you about hearing Black Flag on the radio, but the first moment I was aware of any rock group that you couldn't hear on the radio or find easily in the record store was The Cramps. I saw them on TV in the middle of the night and I was completely mystified by them. The Cramps, just seeing The Cramps, seeing them. I mean, I was electrified by the sound, but seeing them, what they looked like, was a huge thing for me when I was a little kid.

You joined White Zombie after they formed, there's a band when you came in, but, at least from a listener's point of view, the identity thing was still in flux. There wasn't yet a solidified White Zombie aesthetic. What kind of input do you feel you had on the what eventually became the White Zombie sound, or even aesthetically?

You know, it's interesting. I don't know if you're familiar with the earlier White Zombie output

I am

Okay. We're doing something very interesting, we're about to put out a vinyl box set. You know, the last record before I joined the group was called Make Them Die Slowly, and this is kind of a crazy-sounding record..

Yeah, it is

[Laughs] And that record, the way it sounds, is the result of Bill Laswell, a very heavy-handed producer, molding the group according to his taste. And what we're doing with the vinyl box set, is that there's an extra disc, that the first 2000 or something people to buy it are going to get, where we found a different version of that record. Because that record was recorded three different times, which is kind of crazy, and we found a version of that record that's earlier, that doesn't have that crazy production on it. And I think that when you hear that you're going to be able to tell there was sort of a straight line… I mean obviously I brought whatever my style was to the band, and my songwriting, but you hear that there's kind of a more clear progression if you listen to the records chronologically.

So, even though the records before you joined sound more like Butthole Surfers records, to me, than they do any Slayer album, that if I heard that version of the record I would hear how they fit it?

I think so. You know, right when I joined the band, also though, they were making a conscious decision that they wanted to be more of a metal group, and that they wanted to be within the metal scene. This was a conscious decision, and when I met them I was really into metal, so that was great for me. I mean, when I listened to the Soul Crusher record, that guitar playing is crazy, I couldn’t do that. And when they called me, when I initially talked to Rob and Sean, that's what I knew from them, so I just thought: "I can't play that, that's insane! It's like backwards guitar, I can't do that!"

It’s interesting because it isn’t surprising to me at all that there was a conscious decision for White Zombie to be a metal band, because even though there's something about the band that was all over the place, in the festivals, you always played with metal bands. There wasn't any confusion about the fact that White Zombie was a metal band.

That's where the world put us, it isn't entirely true. For example, when we played the famous Castle Donington festival in England, which is a famous metal festival, when we were over there to do that we also plated the Reading Festival, which is not a metal festival, it's much more alternative rock bands. And we were the first band to do both. And I think that's kind of indicative of who we were. Also, do you know about MTV in the 90s?

Yeah, we had MTV in the 90s, just not American MTV. Headbanger's Ball, all that.

Did you have 120 Minutes?

Yes we did, one of my favorite shows.

So, Headbanger's Ball was more of the metal show, and 120 Minutes was the alternative show, and White Zombie was the first group to appear on both shows. So, it's pretty evocative of who we were. You know, when we made La Sexorcisto, and we went to Los Angeles and we met the people from the record company, most of them didn’t know what to make of us, they didn't know what to do with us, in some cases there was hostility toward us and people didn't want to work with us at all. And, they decided we should be a metal band. And, at that time they had different departments, like for radio that they had – they had metal radio and they had alternative radio – and they decided that the person who would try to get our record on the radio was the metal person. And so that's kind of how we became that. And when we went on tour, the gigs were in the metal clubs, not in the alternative clubs, so we became a metal band because we had to be in that category at that time.

Actually, on a personal side note, when you guys played Castle Donnigton, I was 14 and completely clueless as to how things work in the world, and I was convinced that I was going to convince my parents to let me fly out and see you. And, in preparation for this really idiotic idea I even called the British Embassy…

[Laughs]

To find out if there were buses going from the airport, I didn't even know what airport this was, right? It was just "the airport," is there were buses going from the airport to the festival, so I could convince my parents that there was nothing to worry about, and that there were buses and everything, and like midway either through either the conversation or the call I just realized how stupid and hopeless this was, and I just hung up the phone. That festival was my dream.

That's beautiful though, you know? You're a dying breed. There's no such thing as a clueless 13-year-old now. They know everything.

I was as stupid as they come.

You're the last generation that didn't know everything [laughs]. Don't feel bad about it, it's a beautiful thing.

That's kind of true. I was 16 when the Internet came into my life, so I got to be a metalhead without knowing anything about anything. That's interesting because I was just having a conversation with a friend of mine, and he's younger by eight years, which isn't that much, but the difference in who we view music, the obtaining of music, it's as if we're 50 years apart. For me, growing up, listening to metal was always going to be a lonely-island deal, it was always going to be just me doing it, and two other friends that kind of listen to the same bands and would tolerate mine, that was the idea.

And his idea is that it's obvious that it's a community, that it's obvious there's a bunch of people who love that music, and that they get together and… that there are girls in that community…that to me is just…. I mean, he told me there were pretty girls! That can't be! That seems impossible to me, it's only idiot 13-year-olds that call the British Embassy. Those guys don't date.

That's the difference with hardcore, when I was a kid, that there were girls. So, that's a big difference. You should have been a punk [laughs].

Anyway. For me, La Sexorcisto was the culmination of anything that was White Zombie before then. It was the best, to me…. I mean, you guys made a bunch of records before you and after you, and they were great, but that record really kind exemplified how honed your sound became. Maybe it's Andy Wallace's magic hands, but it gave you an identity. And that identity was a metal identity, but it was also loose and you didn't give a fuck.

Yeah, there's a lot of personality on that record.

Yeah, huge personality, and to me, not to knock either, Astro Creep is such a departure from that. And Astro Creep was one of the reasons I wanted to talk to you, right, because it's 20 years to Astro Creep and all that, and it was undoubtedly your biggest success. But when you think about that album as a fan, it's always a sad record, because it's the last one. And it sounded so differently, and it's interesting that you say Andy Wallace produced La Sexorcisto and there's Terry Date on Astro Creep, and it's such a departure, sound wise. And I wanted to ask you what was different about making that album that made it sound so different?

Well, I don't know, we had gear. You've got to understand that during La Sexorcisto I was very poor, I had two pedals, I had one guitar, that whole record is one guitar. I had one amp, I didn’t know anything. I mean, the guitar amp that I owned blew up in the middle of recording, and I had to go get it repaired and get a new tube, and when it came back it sounded completely different. You can hear a different sound between some of the songs. We didn’t have much knowledge about how to make a record. Certainly, we were lucky that Andy Wallace was there.

So, I think the major difference is that we have money and we have time. There's a lot more electronic elements, and I think that the digital thing is something that dates the record a little bit.

Where did that come from?

It's something we wanted to do, we liked samples. There are samples in La Sexorcisto, but it's something that we're doing ourselves and these samples are coming off like old videotapes or old records, whereas on Astro Creep we actually have somebody who does that, who's laying down loops for the songs. I was aware at the time that there needed to be a balance between White Zombie the rockers and the samples and digital elements, and I had to fight quite hard in some cases to keep the band as the dominant sound.

Why?

Rob wanted to do the loop. Rob was so in love with the loops and samples that he just wanted to erase the band. And so I had to be there all the time to make sure that the band was loud, you know? And I'm glad I was, because I think those loops date the record, they put it in the 90s, in a way that La Sexorcisto isn’t really, you can't really identify it with the time period. Astro Creep is the 90s. And I think that if the loops were louder it'd be worse.

I can imagine. I mean, there's an interesting equivalent, that happens to be a Terry Date production too. I mean, I'm a big Prong fan, and early Prong stuff, like Beg To Differ, is really kind of hardcore-y, very guitar-heavy, and then there's Rude Awakening, it's '96. And I love Rude Awakening, I think it's a great album, it almost sounds dated because of the drum machine sound.

The gated reverb, otherwise known as the sound of the 90s.

Yeah, exactly.

They used it very aggressively, and it sounded crazy to us because it's very unfashionable now.

Yeah, it's somehow, again, Astro Creep is one of my favorite albums, but somehow it's so overdone, that it actually sounds good.

[Laughs] I haven't heard it in a while, I should listen to that. You're talking about how the earlier records are more hardcore, more street-sounding, which is true. But I think you have to remember that at the time most of us were the same age, and we're coming from a place where we were into punk and hardcore as very young people, and at that point we're really tying to grow and move beyond that. And [laughs] there are very different results, you know? There are some records from the 90s that sound very very strange to us now, because it's somebody who comes from a punk background trying to do something else. And there are some records that are great and work really well because they're timeless.

We're not obviously against people growing as artists, and if Astro Creep is a culmination of that effort, then that's great, and as that it still holds up, but it's still the last album. So, was there something about that movement toward development that kind of brought out the things that made the band go away eventually?

No, no. I don't think it became apparent until much later that we were going to break up.

It wasn't the making of the album or something like that?

No no, the making of the album was a very positive time. And, as far as my part on it, I'm certainty proud of what I did on that record. People talk to me every day about the guitar sound on that record. It's pretty good.

It's heavy as shit. I mean. It's the heaviest, I mean, it's like a building.

[Laughs] Yeah.

That guitar tone, it's like a fat mattress through a building or something, it's huge.

[Laughs] Yeah, thanks. I would have liked to have made another record, I'm not sure what that would have been like. But, yeah, it seems there should be another record after this. I mean, if you listen to Rob's solo records, you can hear what Astro Creep would have been like had we not been there.

What was it that eventually undid it?

We worked way too hard, we didn’t give ourselves a break, ever. When you're in the system and you have a successful record, everybody around you is pushing you to work as hard as you possibly can. And we just thought that's what you did. And so, we just toured, I don't know, a year and a half or so without really stopping. And also, Rob and Sean's breakup was a huge part of it as well.

Their relationship was kind of what held the band together?

Yeah, I mean it was their band, they started it, and once they weren't a unit, it undermined the group.

It's strange for me, at least, that for a band that was as….. I mean, it seems to me that the 90s are making a sort of comeback

Oh yeah they are, they definitely are.

There's an aesthetic full circle coming here, where a lot of mid-90s albums sound like they fit now. That kind of fat aesthetic is coming back, so it's weird that White Zombie's last album is Supersexy Swingin' Sounds. It's almost unfair.

Yeah, I don't think of that as one of our records. I mean, we didn't work on it. I don't think of it s a White Zombie record, I think of it as a remix record.

Yeah, well. That's what it is. What you're up to now is that you engineer in Waxworks, right? You produce as well?

I do. I mean, I spent…. I mean, pretty soon after the band was over I got into recording.

Why was it you got into recording and not, I don't know, Ozzy Osbourne's guitarist or something?

Well, you know after the group…. I don't know, I think White Zombie is a case of a lot of planets aligning. Like, White Zombie is a real zeitgeist thing, you know what I mean? And it could not have happened the way it did at any other time and with any other people. So, when the band was over, I tried to play with other people for a while, but I realized pretty quickly that I was probably not going to have another group that was…that came together in that same way. I couldn't even figure out what I wanted to play.

And, my experience with the band in the studio was a great one. If you think about it, my very first record with White Zombie was the God of Thunder 12", which we did with Daniel Rey, the famous producer of The Ramones. And then we did some recording with Jim Thirlwell, who's known as Foetus, and who's a famous industrial-music musician. And then we go in with Andy Wallace, who's a fantastic producer, and then we go in with Terry Date, he's a fantastic producer. So, my whole time with the band, I got to watch, I got to work with the top producers, with great people.

Did you find yourself looking at what they were doing? Were you always interested in what they were doing?

Yeah, I always was. And also, especially…. I don't know. When I first started recording with White Zombie, I was very poor, I was almost homeless – I was homeless, for a while – and the studio was a real sanctuary. You imagine, you're poor in New York City is not a good to be. And all of a sudden you're in this amazing place that feels like you're inside a spaceship, and there's blinking lights, and there's confortable couches, whirring tape machine, and the refrigerator's full of food. And you have this producer, who's this very kindly kind of teacher character, and he's there to help you make your art. And this is a very gratifying experience when you're poor, you know?

It's like a metal version of a Charles Dickens novel or something.

Yeah, [laughs] it kind of is. I loved being in the studio. And luckily for me these guys were not only great producers but they were very nice, very benevolent characters. They would answer all my questions, they always showed me exactly what they were doing, and so I kind of, I had this experience with working with real masters of the craft, and I looked at these guys and I thought "Well, that's something I could do when I grow up!"

And, once again, I was at the exactly at the right place at the right time, where right when I became interested in recording there started to be more affordable options for people to record their own music. And so, this is something that started to interest me more than actually playing music.

Is that still the way it is for you? Is it still more interesting for you?

Yeah, it's just as creative. Certainly right now, I've been…somehow I fell into being a mastering engineer, I'm still not quite sure how that happened. It's something that, it's a very esoteric skill. Is there word in Hebrew that’s a good translation for esoteric?

Ahh, we use esoteric as well, so…

Ok, good [laughs] it's something that nobody understands. I mean, my friends were in bands doing this thing and they were like "We need to get this mastered, but it costs so much. Can you figure out how to do it?" And I thought "Yeah, sure, I can do that." And once again, this nearly coincided with the vinyl revolution, and now everybody I know wants to do vinyl but no one knows how to do it.

And you have to skill, it's like you're fated every step of the way. You have a guiding light, not that I want to jinx you or anything.

[Laugh] Yeah, knock on wood. I guess, it seems like that sometimes. It's really big, and certainly it's been a lot of fun over the last two years. I've been working on all kinds of music over the last two years, but the Waxwork thing is a lot of fun, because a huge thing for people my age in America is that when we were young there would be the bargain movie theaters – you could pay like a dollar, and they would show horror movies. And so, when I was a teenager I went to horror movies all the time, and I loved the Misfits, and White Zombie was all about horror movies, and now I'm working on these horror-movie soundtracks, it's very cool.

Yeah, and certainly a lot of these soundtracks come from the original tapes, nobody has heard them outside the movie, so I get to hear these tapes where you can hear the composer counting off the songs and talking about the queues for the movies, it's cool.

I've been following your blog for a while, and you travel quite a bit, and you travel to places where Americans don't travel that much. I know you traveled a lot as a kid, and you toured when you were a musicians, so is that just a continuation of that? Wanting to see more of the world?

Well, yeah, I mean, for me travel is the new rock n' roll, you know? I think for me discovering places, especially places where maybe a lot of people haven't been to yet, it's exactly the same as discovering music when I was younger, it's exactly the same. It's exciting in the same way.

Have you been to Israel?

Not yet, it's on the list.

Do you plan to?

Yeah, I'm definitely coming to Israel.

Umm, it's not un-interesting…

[Laughs] No, I know, I've looked into it. It's near the top of my list.

I think that part of what makes travel and music alike, I think, is that you get to see things for yourself, do things for yourself. Like, even in the environment you described pre-hardcore, where you had to jump through hoops to get a contract, that it was a one-in-a-million chance, even then I would imagine once you picked up a guitar, it looked quite different that what the impossible looked like. And to understand that reality works differently than in fantasy, that's a cool thing. To kind of experience things for yourself.

I wonder, I wonder if people who watch the movie Amelie and then go to Paris and it's nothing like that, I wonder if they think it's a cool for them or not [laughs].

Yeah, the word cool is used here loosely for a very specific kind of experience. I mean, cool for the people who enjoy that kind of stuff, not for the people who watch Rambo and go to Afghanistan.

[Laughs]

I have a few more questions, one of which is kind of random, so I apologize in advance, but – Yuenger, that's not a Jewish name in any way is it?

No, it's German. It's a strange American spelling of a German name.

The reason I asked is that you mentioned when we first spoke that you read Ari Shavit's book, and I was kind of confused as to why anyone who isn't Jewish would read that book.

A lot of Americans would read that book, a lot of non-Jewish Americans would read that book. Well, I mean that probably seems strange to you because you're inside of it. For us, so much of the news comes from Israel. If you're an American then Israel is huge in your world view, and I realized that I didn’t know that much about the country. Probably a lot of people from Israel would have me read something else to learn about the country.

Me included.

[Laughs].

A lot of Americans have Israel in their world view, and it seems to me that not a lot of Americans would read Ari Shavit's book. That's a different kind of curiosity and activity than just listening to the news, it takes more dedication. Do you think it had anything to do with the fact that you grew up in a journalistic home, that you were aware of the world, that you moved around, that you don't take other cultures for granted?

Yeah, probably. I grew up in a family of journalists and I grew up in a very liberal home, and I was exposed to travel at a very young age. And then with the band, we went all over the world. Although we didn't get to play in a lot of the places that bands routinely go now…. I'm sure that's all part of it. For me, personally, when I find out I don't know anything about a country that irritates me and I have to find out.

It's interesting now, another thing with young people who have grown up with the Internet is that travelling…the world is very accessible for them in a way that wasn't for my generation. And when you look at Americans, you see that the younger Americans do travel quite a bit, because they grew up with, like, Anthony Bourdaine on television telling them they should go to Vietnam to eat, you know what I mean? This is a very different setting from my generation.

It's weird to because I'm a young person, I'm 34, I'm not old in any way, and there seems to me to be such a generational gap between and people who are five years younger than me that it's insane. It's almost like being born before the printing press and after.

That's exactly what it's like. You didn't have an iPad in your crib. So there's a fundamental difference between your brain and someone who did, you know?

I like my brain, though.

[Laughs]

I mean, I'm sure my daughter's brain will be great too, I just feel like not noticing the difficulty of things, and the inaccessibility of things, is a real loss, to me. That if you want something you need to kind of get over yourself and your fears and then actually work to get it.

That's a thing people used to do, work for things. That's right. It's old-fashioned, but I like it.

That's the thing, is that it makes me sound as if I'm 60, I'm not 60. The Internet half of my life knows exactly what it's about, and how great it is, the bands, and how I can contact people like you. I mean, when I was 14, talking to you would have been completely impossible. And now it isn't, so there's so much good about it. And yet, I appreciate the fact that I can talk to you also because things were like they were when I was 14.

Well, yeah. When I was a little kid I went to the pawnshop and I got a guitar, and there was nobody to show me how to put strings on it, and there was no way to lean, unless you went to a book shop or the library. And there was nobody to show me how to tune it, so I learned how to play first with a strange alternate tuning, an open tuning, because I didn't know any better, and because I was trying just to play to the Ramones records, because that was the only thing I could figure out.

There was nobody to show you anything, and this is a negative thing, and it's not something I want to go back to. But at the same time, though, there was, and I don't know how much of it is youth, but there's a magic in the world that I think doesn't exist for a lot of people now, because everybody knows everything all the time. So, I think with technological innovation, life is 50 percent better, and 50 percent worse. And when you get into things like some of the arts it may be worse than that, because everyone knows everything all the time. There's no wonder.

I just interviewed a young band from Boston, who I like, a lot, and they play great, they're a great band, I liked them. And one of the things that stood out about them is that they actually sound like a real band. That this sounds like a strange thing to say, because all bands are real bands, but there's this effect of everyone knowing everything, everyone knowing at the moment what's the big "band to be influenced by" right now. So everyone ends up sounding the same, with the same kind of production. The bands that stood out to me when I was a kid, again, like White Zombie, those are to hard to find now, because it's really hard to be insane. Everyone's the same shade of insane.

Yeah, it feels like that now. Maybe in a few years, you know, everything is changing all the time. I can't imagine how it's going to change – it will change, I just can't imagine how at this point. But, yeah, I haven't seen a band in a long time that surprised me in any way. Now, granted I've been seeing bands since 1981, that's a lot of experience. But still you’d think someone would come along and do something that I hadn't thought of.

You know, who actually was one of the last bands to surprise me? It was the Israeli band Monotonix.

Oh yeah? Where did you see them?

I saw them in New Orleans. A friend of mine told me to see this band because they do something completely different, and my friend was right. That band was crazy. Where they spread themselves all over…. I saw them in a big theater, and you know how they did, what they do?

Yeah, they play in the crowd, they go crazy.

Yeah. Generally, I'm not saying this just because you're Israeli. This is one of the last groups I've seen honestly that really surprised me with something different.

I don't know if this is going to make sense. But, for a while there was an American monopoly on rock music. And American got to decide for everyone what was cool and who was successful. And once everyone got to tap into the same source, and It's not just the people who lived in the East Village who knew about the cool music, then the world is de-centralized that way. And while America is still very central and very influential, bands can come up out of nowhere and have that "little town mentality. Because, one of the things I noticed about bands that I liked is that they don't always come from where it's at, and they have to come from the outside and break their way in. And, in a way, international acts can do that now.

They can. I was just thinking about Sepultura, because they were the first band that I met who were from outside of the U.S. or England or Europe. They were the very first ones. And I remember talking to them and then telling me: "We're a third-world band. The third world is our world." And they would play concerts in like South America, in Chile, places where no bands went. And I remember in that time, in the 90s, when I was on tour and we went to all the standard places, it was like: "Oh, we're playing in Holland, again." I know playing in a band, it sounds glamorous, but you just play in Holland a lot. And I remember these guys would go and play India, and I would be "God, I want to play in India!" And nothing like that ever happened to me. Maybe that's why I want to travel so much, because I missed going to these places.

So Sepultura owned the fact that they weren't American, they weren’t trying to be, I don't know, the next Slayer but to be the first Sepultura? Just because they were from Brazil?

Well, I think that was such a cool part of their identity. In fact, I remember the first multi-cultural experience I had in rock music, outside of people meeting people from England or Europe, was I met the guys from Sepultura at the exact same time that I met the guys from Voivod. And the guys from Voivod, they're from French Canada, so they don't really speak English, and the guys from Sepultura couldn't really speak English, and obviously they couldn’t talk with each other either. And I remember standing there with them, and we’re all trying to talk to each other and it's not working, it’s all sign language. That was a funny time.

That's insane.

[Laughs] Yeah, it's fucking great.

Where was that? Some kind of festival?

Yeah, I think it was at the CMJ convention in New York City. This would have been in the very early 90s, maybe '90 or '91. And I know that it was Sepultura's first time in America, so whenever they first came to New York.